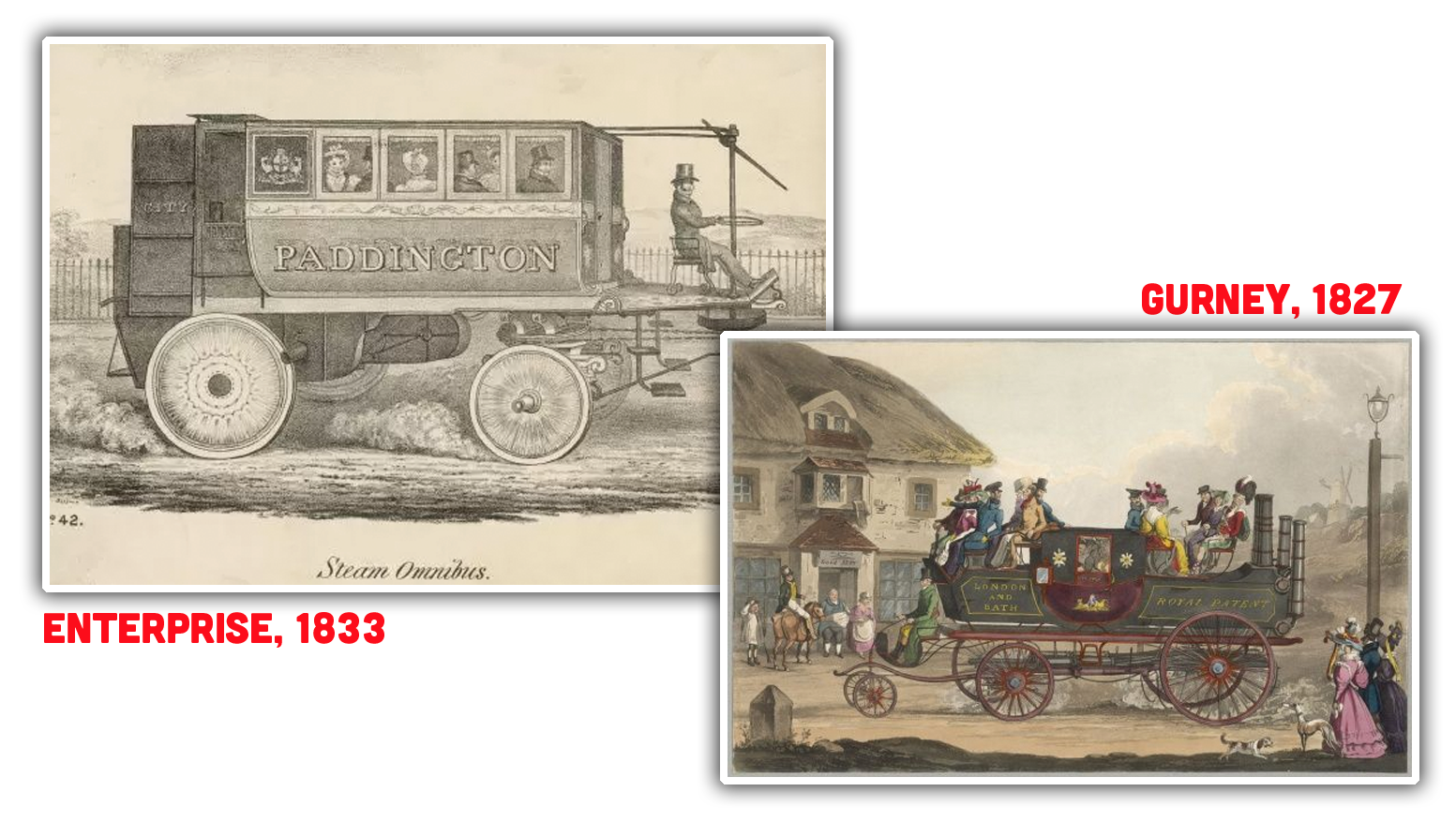

I picked the Enterprise to start this series because it was part of what can be considered the first real commercialized boom of automobiles, starting in the late 1820s and going into the 1830s. This first real commercial application of the automobile was as bus service in and around London. There was a number of automobiles developed prior to this boom, but they were generally experimental one-off machines that would only have been operated or even ridden in by a pretty small and select group of people. The first time any member of the general public, not directly involved with the development or funding of automobile projects in some way, could have any sort of real access to travel by automobile was in London in the 1830s. There were plenty of people and companies building steam-powered omnibuses (that’s just a dated term for “bus”) with the intent to provide mass transit to Londoners. Horse-drawn omnibuses had been introduced to London in 1829 by George Shillibeer, who had previously been contracted to build similar mass-transit horse-carriages in Paris. The fact that it only took two years after the introduction of horse-pulled buses for motorized bus service to appear in London is pretty incredible, and the man who started the first regular automobile bus service was Walter Hancock, with his bus, hilariously named the Infant. The smallish, 10-seat Infant was actually built in 1829, and started regular service between Stratford and central London in 1831. It then began doing regular, money-earning runs from London to Brighton. Later, in 1833, we’re introduced to the voyages of the steam bus Enterprise, which had a continuing mission to explore strange new routes (well, mostly the route between London and Paddington via Islington), seek out new fares and passengers, and boldly go where no steam bus had gone before. The Enterprise is an especially interesting bus of this era because of the relative refinement and sophistication of its design. Where slightly earlier steam omnibuses, like the famous ones from Goldsworthy Gurney, looked and seemed like mechanically-adapted horse carriages, the Enterprise really seemed like something completely new unto itself, after only a few years of difference in age. Here, let’s compare:

Look at the difference there! The 1827 Gurney looks like a normal carriage plopped onto a longer chassis, with the steam engine slung out back and passengers just stuck on top, wherever some benches could be bolted. It looks like a design that just sort of happened, as opposed to following some master plan. The Enterprise, on the other hand, is essentially shaped the same as a modern bus is today: a box on wheels (with seating for 14) with the engine mounted at the rear, and the rest of the drivetrain below.

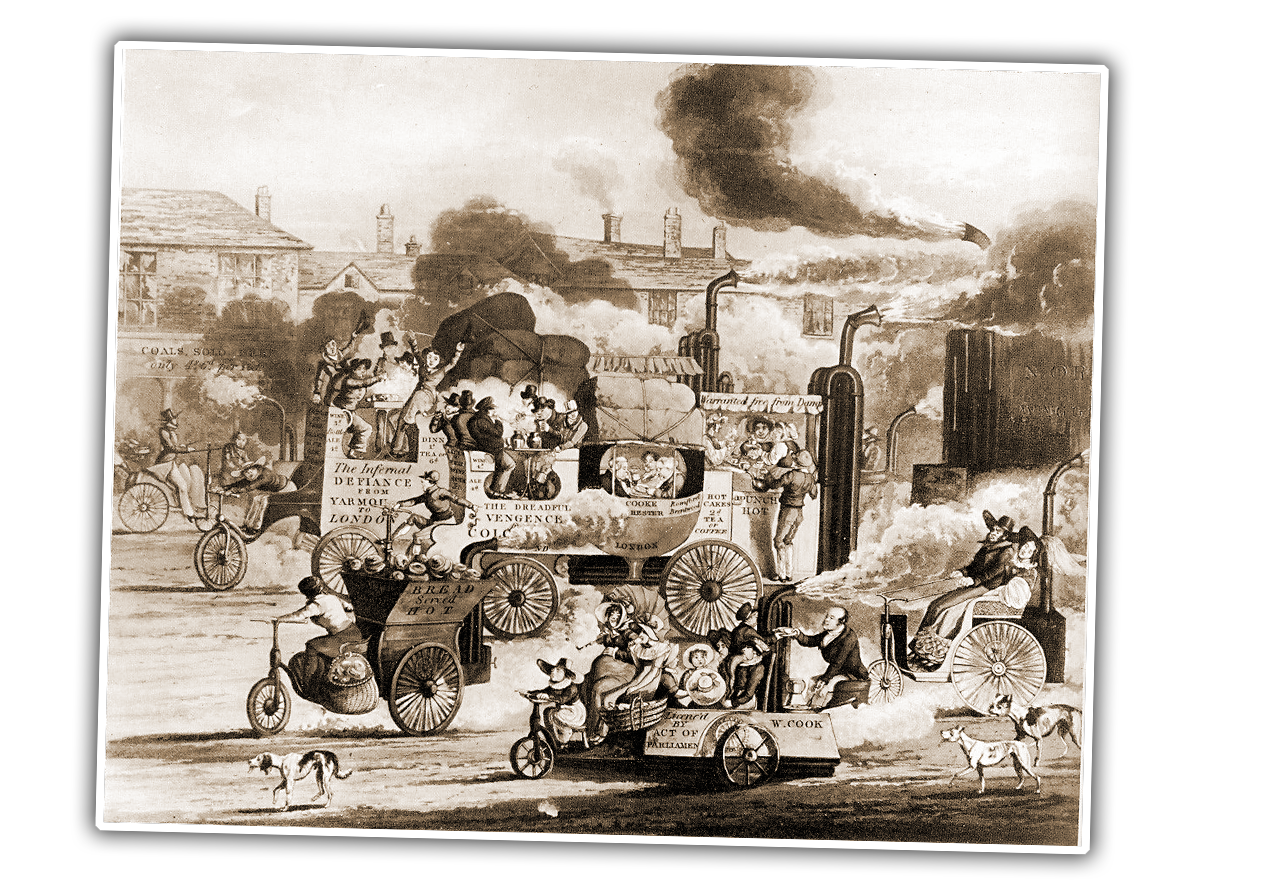

The Enterprise was full of advanced features: full leaf-sprung suspension for all wheels, a twin-vertical-cylinder engine capable of running at 100 RPM and able to drive the rear axle directly below it in quite a compact (for the time) setup; it burned coke instead of coal (coke burns hotter and cleaner) and even had a crankshaft-driven fan to help keep exhaust from becoming too obtrusive. For 1833, this was some state-of-the-art shit. Unlike modern buses, though, it took three people to drive the Enterprise: the driver, who steers the bus with the large, horizontal steering wheel and controls the speed via a regulator; an engine tender at the rear who maintained the water level of the boiler; and someone to attend to the boiler’s fire and to also control a brake handle, which was used to keep speed controllable down hills. There’s no obvious answer to how the team of three would have communicated as the vehicle drove, which could be as fast as 20 mph. What’s incredible is that these early automobiles had the potential to be genuinely competitive with horse-powered omnibuses of the era. They were less likely to overturn, were cheaper to operate, and caused less damage to roads than horse hooves. Steam buses were also less likely to continue to attempt to pull a carriage with brakes locked, since they lacked independent horse brains that might make decisions counter to what the driver wanted. In the early 1830s steam buses were becoming so well known that they inspired popular culture works like this famous (well, to early 1800s car geeks) cartoon:

I’ve written about this cartoon before–I had thought it was from the British satirical magazine Punch, but Punch was founded in 1841, and this is from 1831. The cartoon is titled A View in Whitechapel Road and was drawn by H.T. Aiken. It shows what is, essentially, a traffic jam, of automobiles, buses and private cars and commercial vehicles, some of which have names like The Infernal Defiance and The Dreadful Vengance, and there’s a hot bread-vending truck that I bet smells great. Also interesting to note is the depiction of pollution from all these vehicles, shown by their billowing clouds of steam and smoke. It appears to be exaggerated, indicating that smog was a concern even back in the 1830s. Hancock was able to operate a bus service with the Enterprise and other buses, including one called, bafflingly, Autopsy, and others called Era (I and II, even) and Automaton, which could seat 22. Technically, the steam buses performed quite well, and put up impressive numbers: Hancock’s buses travelled 4,200 miles, carried 12,761 passengers, made 143 round trips from London to Paddington, 525 trips from London to Islington, and 44 to Stratford. Despite this, making money with them proved extremely difficult, because the powerful Horse Carriage Lobby (that was a thing) and Turnpike Trusts (organizations of road owners) did all they could to impede the progress of steam buses, legal and otherwise. For example, on some roads, road tolls were 4 shillings for horse-drawn coaches, while they were 48 shillings for steam vehicles. They really couldn’t win, and this was even before the famously restrictive “Red Flag Acts” enacted by Parliament in 1865 that severely restricted automotive development in the UK for years. By 1840 Hancock was out of the automobile-based mass transit game, which is a shame, because he really seemed to be doing a lot to further the overall development of the automobile. These buses were really the first access to cars normal people would get, and the way Hancock was developing them could have led to mass-market cars decades earlier, or at least my overactive imagination claims.

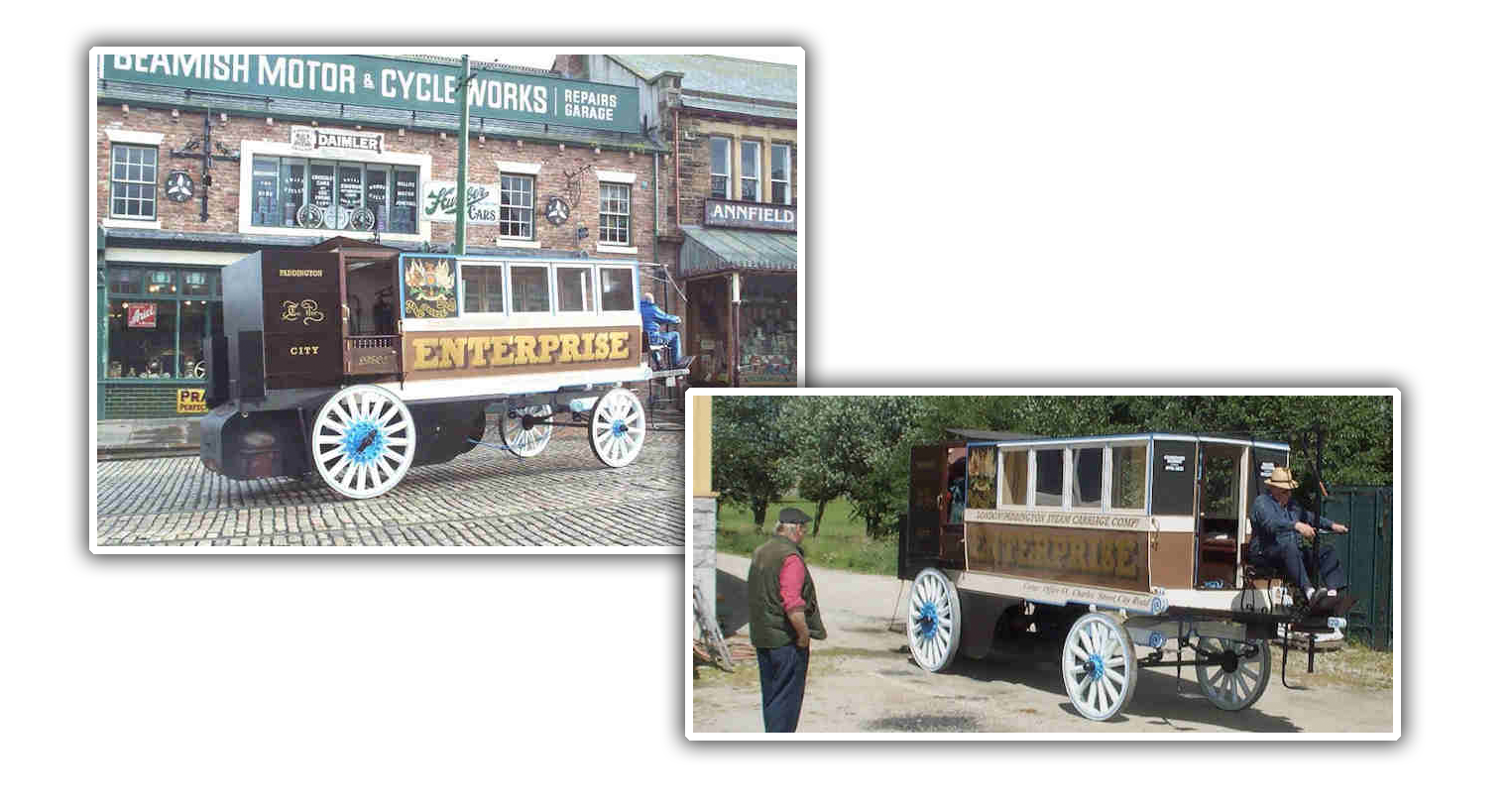

It’s also worth noting that Hancock kept excellent records and drawings of his designs, and using those a replica of the Enterprise was built by some extremely dedicated enthusiasts, as you can see above there.

This era of automotive development doesn’t get a lot of mass-media attention, but it absolutely should. The first boom era for automobiles was the 1830s, and it’s high time more people realized that.

Was the purpose of the fan really to help get rid of exhaust smoke? Before the blast pipe came into common usage, it was normal to have a blower of some sort on a steam engine for the purpose of moving more air over the fire and improving combustion.

The history of using coke and coal is worth an article by itself. Coke was the primary fuel for British steam engines until the late 19th century. The advantages of reduced smoke and reduced coking in the engine largely made up for its higher cost. These were especially important on urban railways and especially especially important for undergrounds.

… yes I’m using that as an excuse to test something (and post relevant things.)

What do you have against tail lights?!?

In fairness, this is more useful-adjacent than Jason’s think piece from That Other Site about what cars would look like if they were designed by and for squids. (Which was brilliant, BTW.)

So rolling coal has been despised for close to 189 years now.

Karl Benz was probably the first person to think up of patenting the automobile. That patent was widely regarded as the “world’s first PRACTICAL automobile” that has features found in the modern automobiles today and can be operated by the “everyday” person. It doesn’t imply that his Patentwagen was the “first car” to be invented.

Oh, wait, his deeply frustrated wife, Bretha, “promoted” his car by participating in the world’s first road trip (travelling between cities) and first joyride (she took the Patentwagen without his knowledge or permission). Her road trip ensued the free advertisement and forced her husband to start the sales of his Patentwagen. Thus, the first “practical” automobile to be put into SERIES PRODUCTION and sold to the public for personal/private use.

By the way, Mercedes-Benz did not exist until the merger of Daimler and Benz in 1886 to form the Daimler-Benz AG. Mercedes-Benz was (and still is) the sales arm of Daimler-Benz AG then DaimlerChrysler then Daimler AG then currently Mercedes-Benz Group. So, you’re totally wrong, Jason, here.

The steam car from 1796 was just one-off vehicle that was totally impractical with massive and temperamental steam engine and lack of steering ability or suspension. Would that describe the “modern car”? No, not by long stretch! Of course, the steam car fans would insist that the steam cars were the first one. Fine, how many were put into the regular production and bought by the private owners?

Eh, not quite right. FYI, I’m a registered patent agent.

The names listed on the patent must be the inventors. These are the people who if the patent is ever litigated will be disposed by the lawyers and grilled about their knowledge of the invention, how they came up with, what was the motivation, etc.

The legal rights to a patent can be assigned to others, including corporations. These are assignees, though, and while they may be listed on the patent, they do not replace the inventors. Inventors need to sign statements (oaths or declarations) that they, and only they, came up with the invention. If you work for a company that patents ideas, then you will most likely be forced to sign a statement that all your work related ideas belong to the company in exchange for a paycheck. But if you come up with an idea, you will still be listed as an inventor on a patent that the company files in your name.

Did you know a similar thing happened with motorcycles? Three different designs appeared at about 1885/6*. No one knows or has proof of who was first, but based purely on a technicality the ‘experts’ have decided the gas powered one automatically wins. Personally i think the steam powered Michaux-Perreaux should at least have equal billing.

Yes i’m a little biased.I’ve seen it up close and i’m in love.It’s one of the most interesting machines i’ve ever seen! The mechanicals and detailing are so complex i was finding new things after staring at it for 10 minutes. If you ever get a chance to see it up close, run don’t walk, don’t miss the chance! You’ve seen lots of fascinating machines in your time so it may not interest you as it did me, but it will still give you a buzz 😀

- Actually there was a steam powered motorcycle many years previously and the experts have decided that one doesnt count either.But that’s a whole other side argument https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=03Kb5r7MHXE&ab_channel=Sandy- -Someone whose high school principal was fired for messing around with a student, which I later found out was not the first time he had done that.